Administration and commerce

The pharaoh was the absolute monarch of the country and, at least in theory, wielded complete control of the land and its resources. The king was the supreme military commander and head of the government, who relied on a bureaucracy of officials to manage his affairs. In charge of the administration was his second in command, the vizier, who acted as the king's representative and coordinated land surveys, the treasury, building projects, the legal system, and the archives.[68] At a regional level, the country was divided into as many as 42 administrative regions called nomes each governed by a nomarch, who was accountable to the vizier for his jurisdiction. The temples formed the backbone of the economy. Not only were they houses of worship, but were also responsible for collecting and storing the nation's wealth in a system of granaries and treasuries administered by overseers, who redistributed grain and goods.[69]

Much of the economy was centrally organized and strictly controlled. Although the ancient Egyptians did not use coinage until the Late period, they did use a type of money-barter system,[70] with standard sacks of grain and the deben, a weight of roughly 91 grams (3 oz) of copper or silver, forming a common denominator.[71] Workers were paid in grain; a simple laborer might earn 5½ sacks (200 kg or 400 lb) of grain per month, while a foreman might earn 7½ sacks (250 kg or 550 lb). Prices were fixed across the country and recorded in lists to facilitate trading; for example a shirt cost five copper deben, while a cow cost 140 deben.[71] Grain could be traded for other goods, according to the fixed price list.[71] During the 5th century BC coined money was introduced into Egypt from abroad. At first the coins were used as standardized pieces of precious metal rather than true money, but in the following centuries international traders came to rely on coinage.[72]

Social status

Egyptian society was highly stratified, and social status was expressly displayed. Farmers made up the bulk of the population, but agricultural produce was owned directly by the state, temple, or noble family that owned the land.[73] Farmers were also subject to a labor tax and were required to work on irrigation or construction projects in a corvée system.[74] Artists and craftsmen were of higher status than farmers, but they were also under state control, working in the shops attached to the temples and paid directly from the state treasury. Scribes and officials formed the upper class in ancient Egypt, the so-called "white kilt class" in reference to the bleached linen garments that served as a mark of their rank.[75] The upper class prominently displayed their social status in art and literature. Below the nobility were the priests, physicians, and engineers with specialized training in their field. Slavery was known in ancient Egypt, but the extent and prevalence of its practice are unclear.[76]

The ancient Egyptians viewed men and women, including people from all social classes except slaves, as essentially equal under the law, and even the lowliest peasant was entitled to petition the vizier and his court for redress.[77] Both men and women had the right to own and sell property, make contracts, marry and divorce, receive inheritance, and pursue legal disputes in court. Married couples could own property jointly and protect themselves from divorce by agreeing to marriage contracts, which stipulated the financial obligations of the husband to his wife and children should the marriage end. Compared with their counterparts in ancient Greece, Rome, and even more modern places around the world, ancient Egyptian women had a greater range of personal choices and opportunities for achievement. Women such as Hatshepsut and Cleopatra even became pharaohs, while others wielded power as Divine Wives of Amun. Despite these freedoms, ancient Egyptian women did not often take part in official roles in the administration, served only secondary roles in the temples, and were not as likely to be as educated as men.[77] Also see a BBC History article online for more information on gender equality in ancient Egypt.[78]

Legal system

The head of the legal system was officially the pharaoh, who was responsible for enacting laws, delivering justice, and maintaining law and order, a concept the ancient Egyptians referred to as Ma'at.[68] Although no legal codes from ancient Egypt survive, court documents show that Egyptian law was based on a common-sense view of right and wrong that emphasized reaching agreements and resolving conflicts rather than strictly adhering to a complicated set of statutes.[77] Local councils of elders, known as Kenbet in the New Kingdom, were responsible for ruling in court cases involving small claims and minor disputes.[68] More serious cases involving murder, major land transactions, and tomb robbery were referred to the Great Kenbet, over which the vizier or pharaoh presided. Plaintiffs and defendants were expected to represent themselves and were required to swear an oath that they had told the truth. In some cases, the state took on both the role of prosecutor and judge, and it could torture the accused with beatings to obtain a confession and the names of any co-conspirators. Whether the charges were trivial or serious, court scribes documented the complaint, testimony, and verdict of the case for future reference.[79]

Punishment for minor crimes involved either imposition of fines, beatings, facial mutilation, or exile, depending on the severity of the offense. Serious crimes such as murder and tomb robbery were punished by execution, carried out by decapitation, drowning, or impaling the criminal on a stake. Punishment could also be extended to the criminal's family.[68] Beginning in the New Kingdom, oracles played a major role in the legal system, dispensing justice in both civil and criminal cases. The procedure was to ask the god a "yes" or "no" question concerning the right or wrong of an issue. The god, carried by a number of priests, rendered judgment by choosing one or the other, moving forward or backward, or pointing to one of the answers written on a piece of papyrus or an ostracon.[80]

Agriculture

See also: Ancient Egyptian cuisine

A combination of favorable geographical features contributed to the success of ancient Egyptian culture, the most important of which was the rich fertile soil resulting from annual inundations of the Nile River. The ancient Egyptians were thus able to produce an abundance of food, allowing the population to devote more time and resources to cultural, technological, and artistic pursuits. Land management was crucial in ancient Egypt because taxes were assessed based on the amount of land a person owned.[81]

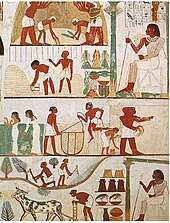

Farming in Egypt was dependent on the cycle of the Nile River. The Egyptians recognized three seasons: Akhet (flooding), Peret (planting), and Shemu (harvesting). The flooding season lasted from June to September, depositing on the river's banks a layer of mineral-rich silt ideal for growing crops. After the floodwaters had receded, the growing season lasted from October to February. Farmers plowed and planted seeds in the fields, which were irrigated with ditches and canals. Egypt received little rainfall, so farmers relied on the Nile to water their crops.[82] From March to May, farmers used sickles to harvest their crops, which were then threshed with a flail to separate the straw from the grain. Winnowing removed the chaff from the grain, and the grain was then ground into flour, brewed to make beer, or stored for later use.[83]

The ancient Egyptians cultivated emmer and barley, and several other cereal grains, all of which were used to make the two main food staples of bread and beer.[84] Flax plants, uprooted before they started flowering, were grown for the fibers of their stems. These fibers were split along their length and spun into thread, which was used to weave sheets of linen and to make clothing. Papyrus growing on the banks of the Nile River was used to make paper. Vegetables and fruits were grown in garden plots, close to habitations and on higher ground, and had to be watered by hand. Vegetables included leeks, garlic, melons, squashes, pulses, lettuce, and other crops, in addition to grapes that were made into wine.[85]

Farming in Egypt was dependent on the cycle of the Nile River. The Egyptians recognized three seasons: Akhet (flooding), Peret (planting), and Shemu (harvesting). The flooding season lasted from June to September, depositing on the river's banks a layer of mineral-rich silt ideal for growing crops. After the floodwaters had receded, the growing season lasted from October to February. Farmers plowed and planted seeds in the fields, which were irrigated with ditches and canals. Egypt received little rainfall, so farmers relied on the Nile to water their crops.[82] From March to May, farmers used sickles to harvest their crops, which were then threshed with a flail to separate the straw from the grain. Winnowing removed the chaff from the grain, and the grain was then ground into flour, brewed to make beer, or stored for later use.[83]

The ancient Egyptians cultivated emmer and barley, and several other cereal grains, all of which were used to make the two main food staples of bread and beer.[84] Flax plants, uprooted before they started flowering, were grown for the fibers of their stems. These fibers were split along their length and spun into thread, which was used to weave sheets of linen and to make clothing. Papyrus growing on the banks of the Nile River was used to make paper. Vegetables and fruits were grown in garden plots, close to habitations and on higher ground, and had to be watered by hand. Vegetables included leeks, garlic, melons, squashes, pulses, lettuce, and other crops, in addition to grapes that were made into wine.[85]

Animals

The Egyptians believed that a balanced relationship between people and animals was an essential element of the cosmic order; thus humans, animals and plants were believed to be members of a single whole.[86] Animals, both domesticated and wild, were therefore a critical source of spirituality, companionship, and sustenance to the ancient Egyptians. Cattle were the most important livestock; the administration collected taxes on livestock in regular censuses, and the size of a herd reflected the prestige and importance of the estate or temple that owned them. In addition to cattle, the ancient Egyptians kept sheep, goats, and pigs. Poultry such as ducks, geese, and pigeons were captured in nets and bred on farms, where they were force-fed with dough to fatten them.[87] The Nile provided a plentiful source of fish. Bees were also domesticated from at least the Old Kingdom, and they provided both honey and wax.[88]

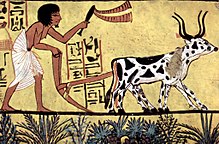

The ancient Egyptians used donkeys and oxen as beasts of burden, and they were responsible for plowing the fields and trampling seed into the soil. The slaughter of a fattened ox was also a central part of an offering ritual.[87] Horses were introduced by the Hyksos in the Second Intermediate Period, and the camel, although known from the New Kingdom, was not used as a beast of burden until the Late Period. There is also evidence to suggest that elephants were briefly utilized in the Late Period, but largely abandoned due to lack of grazing land.[87] Dogs, cats and monkeys were common family pets, while more exotic pets imported from the heart of Africa, such as lions, were reserved for royalty. Herodotus observed that the Egyptians were the only people to keep their animals with them in their houses.[86] During the Predynastic and Late periods, the worship of the gods in their animal form was extremely popular, such as the cat goddess Bastet and the ibis god Thoth, and these animals were bred in large numbers on farms for the purpose of ritual sacrifice.[89]

Natural resources

Further information: Mining in Egypt

Egypt is rich in building and decorative stone, copper and lead ores, gold, and semiprecious stones. These natural resources allowed the ancient Egyptians to build monuments, sculpt statues, make tools, and fashion jewelry.[90] Embalmers used salts from the Wadi Natrun for mummification, which also provided the gypsum needed to make plaster.[91] Ore-bearing rock formations were found in distant, inhospitable wadis in the eastern desert and the Sinai, requiring large, state-controlled expeditions to obtain natural resources found there. There were extensive gold mines in Nubia, and one of the first maps known is of a gold mine in this region. The Wadi Hammamat was a notable source of granite, greywacke, and gold. Flint was the first mineral collected and used to make tools, and flint handaxes are the earliest pieces of evidence of habitation in the Nile valley. Nodules of the mineral were carefully flaked to make blades and arrowheads of moderate hardness and durability even after copper was adopted for this purpose.[92]

The Egyptians worked deposits of the lead ore galena at Gebel Rosas to make net sinkers, plumb bobs, and small figurines. Copper was the most important metal for toolmaking in ancient Egypt and was smelted in furnaces from malachite ore mined in the Sinai.[93] Workers collected gold by washing the nuggets out of sediment in alluvial deposits, or by the more labor-intensive process of grinding and washing gold-bearing quartzite. Iron deposits found in upper Egypt were utilized in the Late Period.[94] High-quality building stones were abundant in Egypt; the ancient Egyptians quarried limestone all along the Nile valley, granite from Aswan, and basalt and sandstone from the wadis of the eastern desert. Deposits of decorative stones such as porphyry, greywacke, alabaster, and carnelian dotted the eastern desert and were collected even before the First Dynasty. In the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods, miners worked deposits of emeralds in Wadi Sikait and amethyst in Wadi el-Hudi.[95]

Trade

The ancient Egyptians engaged in trade with their foreign neighbors to obtain rare, exotic goods not found in Egypt. In the Predynastic Period, they established trade with Nubia to obtain gold and incense. They also established trade with Palestine, as evidenced by Palestinian-style oil jugs found in the burials of the First Dynasty pharaohs.[96] An Egyptian colony stationed in southern Canaan dates to slightly before the First Dynasty.[97] Narmer had Egyptian pottery produced in Canaan and exported back to Egypt.[98]

By the Second Dynasty at latest, ancient Egyptian trade with Byblos yielded a critical source of quality timber not found in Egypt. By the Fifth Dynasty, trade with Punt provided gold, aromatic resins, ebony, ivory, and wild animals such as monkeys and baboons.[99] Egypt relied on trade with Anatolia for essential quantities of tin as well as supplementary supplies of copper, both metals being necessary for the manufacture of bronze. The ancient Egyptians prized the blue stone lapis lazuli, which had to be imported from far-away Afghanistan. Egypt's Mediterranean trade partners also included Greece and Crete, which provided, among other goods, supplies of olive oil.[100] In exchange for its luxury imports and raw materials, Egypt mainly exported grain, gold, linen, and papyrus, in addition to other finished goods including glass and stone objects.[101]

Language

Main article: Egyptian language

Historical development

The Egyptian language is a northern Afro-Asiatic language closely related to the Berber and Semitic languages.[102] It has the second longest history of any language (after Sumerian), having been written from c. 3200 BC to the Middle Ages and remaining as a spoken language for longer. The phases of Ancient Egyptian are Old Egyptian, Middle Egyptian (Classical Egyptian), Late Egyptian, Demotic and Coptic.[103] Egyptian writings do not show dialect differences before Coptic, but it was probably spoken in regional dialects around Memphis and later Thebes.[104]

Ancient Egyptian was a synthetic language, but it became more analytic later on. Late Egyptian develops prefixal definite and indefinite articles, which replace the older inflectional suffixes. There is a change from the older Verb Subject Object word order to Subject Verb Object.[105] The Egyptian hieroglyphic, hieratic, and demotic scripts were eventually replaced by the more phonetic Coptic alphabet. Coptic is still used in the liturgy of the Egyptian Orthodox Church, and traces of it are found in modern Egyptian Arabic.[106]

Sounds and grammar

Ancient Egyptian has 25 consonants similar to those of other Afro-Asiatic languages. These include pharyngeal and emphatic consonants, voiced and voiceless stops, voiceless fricatives and voiced and voiceless affricates. It has three long and three short vowels, which expanded in Later Egyptian to about nine.[107] The basic word in Egyptian, similar to Semitic and Berber, is a triliteral or biliteral root of consonants and semiconsonants. Suffixes are added to form words. The verb conjugation corresponds to the person. For example, the triconsonantal skeleton S-Ḏ-M is the semantic core of the word 'hear'; its basic conjugation is {{{2}}} 'he hears'. If the subject is a noun, suffixes are not added to the verb:[108] sḏm ḥmt 'the woman hears'.

Adjectives are derived from nouns through a process that Egyptologists call nisbation because of its similarity with Arabic.[109] The word order is PREDICATE-SUBJECT in verbal and adjectival sentences, and SUBJECT-PREDICATE in nominal and adverbial sentences.[110] The subject can be moved to the beginning of sentences if it is long and is followed by a resumptive pronoun.[111] Verbs and nouns are negated by the particle n, but nn is used for adverbial and adjectival sentences. Stress falls on the ultimate or penultimate syllable, which can be open (CV) or closed (CVC).[112]

Writing

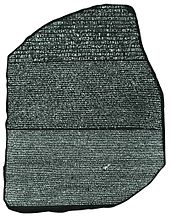

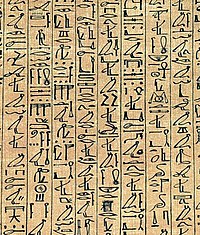

Hieroglyphic Writing dates to c. 3200 BC, and is composed of some 500 symbols. A hieroglyph can represent a word, a sound, or a silent determinative; and the same symbol can serve different purposes in different contexts. Hieroglyphs were a formal script, used on stone monuments and in tombs, that could be as detailed as individual works of art. In day-to-day writing, scribes used a cursive form of writing, called hieratic, which was quicker and easier. While formal hieroglyphs may be read in rows or columns in either direction (though typically written from right to left), hieratic was always written from right to left, usually in horizontal rows. A new form of writing, Demotic, became the prevalent writing style, and it is this form of writing—along with formal hieroglyphs—that accompany the Greek text on the Rosetta Stone.[citation needed

Around the 1st century AD, the Coptic alphabet started to be used alongside the Demotic script. Coptic is a modified Greek alphabet with the addition of some Demotic signs.[114] Although formal hieroglyphs were used in a ceremonial role until the 4th century AD, towards the end only a small handful of priests could still read them. As the traditional religious establishments were disbanded, knowledge of hieroglyphic writing was mostly lost. Attempts to decipher them date to the Byzantine[115] and Islamic periods in Egypt,[116] but only in 1822, after the discovery of the Rosetta stone and years of research by Thomas Young and Jean-François Champollion, were hieroglyphs almost fully deciphered.[117]

Literature

Main article: Ancient Egyptian literature

Writing first appeared in association with kingship on labels and tags for items found in royal tombs. It was primarily an occupation of the scribes, who worked out of the Per Ankh institution or the House of Life. The latter comprised offices, libraries (called House of Books), laboratories and observatories.[118] Some of the best-known pieces of ancient Egyptian literature, such as the Pyramid and Coffin Texts, were written in Classical Egyptian, which continued to be the language of writing until about 1300 BC. Later Egyptian was spoken from the New Kingdom onward and is represented in Ramesside administrative documents, love poetry and tales, as well as in Demotic and Coptic texts. During this period, the tradition of writing had evolved into the tomb autobiography, such as those of Harkhuf and Weni. The genre known as Sebayt (Instructions) was developed to communicate teachings and guidance from famous nobles; the Ipuwer papyrus, a poem of lamentations describing natural disasters and social upheaval, is a famous example.

The Story of Sinuhe, written in Middle Egyptian, might be the classic of Egyptian literature.[119] Also written at this time was the Westcar Papyrus, a set of stories told to Khufu by his sons relating the marvels performed by priests.[120] The Instruction of Amenemope is considered a masterpiece of near-eastern literature.[121] Towards the end of the New Kingdom, the vernacular language was more often employed to write popular pieces like the Story of Wenamun and the Instruction of Any. The former tells the story of a noble who is robbed on his way to buy cedar from Lebanon and of his struggle to return to Egypt. From about 700 BC, narrative stories and instructions, such as the popular Instructions of Onchsheshonqy, as well as personal and business documents were written in the demotic script and phase of Egyptian. Many stories written in demotic during the Graeco-Roman period were set in previous historical eras, when Egypt was an independent nation ruled by great pharaohs such as Ramesses II.[122]

The Story of Sinuhe, written in Middle Egyptian, might be the classic of Egyptian literature.[119] Also written at this time was the Westcar Papyrus, a set of stories told to Khufu by his sons relating the marvels performed by priests.[120] The Instruction of Amenemope is considered a masterpiece of near-eastern literature.[121] Towards the end of the New Kingdom, the vernacular language was more often employed to write popular pieces like the Story of Wenamun and the Instruction of Any. The former tells the story of a noble who is robbed on his way to buy cedar from Lebanon and of his struggle to return to Egypt. From about 700 BC, narrative stories and instructions, such as the popular Instructions of Onchsheshonqy, as well as personal and business documents were written in the demotic script and phase of Egyptian. Many stories written in demotic during the Graeco-Roman period were set in previous historical eras, when Egypt was an independent nation ruled by great pharaohs such as Ramesses II.[122]

Culture

Daily life

Most ancient Egyptians were farmers tied to the land. Their dwellings were restricted to immediate family members, and were constructed of mud-brick designed to remain cool in the heat of the day. Each home had a kitchen with an open roof, which contained a grindstone for milling flour and a small oven for baking bread.[123] Walls were painted white and could be covered with dyed linen wall hangings. Floors were covered with reed mats, while wooden stools, beds raised from the floor and individual tables comprised the furniture.[124]

The ancient Egyptians placed a great value on hygiene and appearance. Most bathed in the Nile and used a pasty soap made from animal fat and chalk. Men shaved their entire bodies for cleanliness, and aromatic perfumes and ointments covered bad odors and soothed skin.[125] Clothing was made from simple linen sheets that were bleached white, and both men and women of the upper classes wore wigs, jewelry, and cosmetics. Children went without clothing until maturity, at about age 12, and at this age males were circumcised and had their heads shaved. Mothers were responsible for taking care of the children, while the father provided the family's income.[126]

Music and dance were popular entertainments for those who could afford them. Early instruments included flutes and harps, while instruments similar to trumpets, oboes, and pipes developed later and became popular. In the New Kingdom, the Egyptians played on bells, cymbals, tambourines, and drums and imported lutes and lyres from Asia.[127] The sistrum was a rattle-like musical instrument that was especially important in religious ceremonies.

The ancient Egyptians enjoyed a variety of leisure activities, including games and music. Senet, a board game where pieces moved according to random chance, was particularly popular from the earliest times; another similar game was mehen, which had a circular gaming board. Juggling and ball games were popular with children, and wrestling is also documented in a tomb at Beni Hasan.[128] The wealthy members of ancient Egyptian society enjoyed hunting and boating as well.

The excavation of the workers village of Deir el-Madinah has resulted in one of the most thoroughly documented accounts of community life in the ancient world that spans almost four hundred years. There is no comparable site in which the organisation, social interactions, working and living conditions of a community can be studied in such detail.[129]

Cuisine

Main article: Ancient Egyptian cuisine

Egyptian cuisine remained remarkably stable over time; indeed, the cuisine of modern Egypt retains some striking similarities to the cuisine of the ancients. The staple diet consisted of bread and beer, supplemented with vegetables such as onions and garlic, and fruit such as dates and figs. Wine and meat were enjoyed by all on feast days while the upper classes indulged on a more regular basis. Fish, meat, and fowl could be salted or dried, and could be cooked in stews or roasted on a grill.[130]

Architecture

Main article: Ancient Egyptian architecture

The architecture of ancient Egypt includes some of the most famous structures in the world: the Great Pyramids of Giza and the temples at Thebes. Building projects were organized and funded by the state for religious and commemorative purposes, but also to reinforce the power of the pharaoh. The ancient Egyptians were skilled builders; using simple but effective tools and sighting instruments, architects could build large stone structures with accuracy and precision.[131]

The domestic dwellings of elite and ordinary Egyptians alike were constructed from perishable materials such as mud bricks and wood, and have not survived. Peasants lived in simple homes, while the palaces of the elite were more elaborate structures. A few surviving New Kingdom palaces, such as those in Malkata and Amarna, show richly decorated walls and floors with scenes of people, birds, water pools, deities and geometric designs.[132] Important structures such as temples and tombs that were intended to last forever were constructed of stone instead of bricks. The architectural elements used in the world's first large-scale stone building, Djoser's mortuary complex, include post and lintel supports in the papyrus and lotus motif.

The earliest preserved ancient Egyptian temples, such as those at Giza, consist of single, enclosed halls with roof slabs supported by columns. In the New Kingdom, architects added the pylon, the open courtyard, and the enclosed hypostyle hall to the front of the temple's sanctuary, a style that was standard until the Graeco-Roman period.[133] The earliest and most popular tomb architecture in the Old Kingdom was the mastaba, a flat-roofed rectangular structure of mudbrick or stone built over an underground burial chamber. The step pyramid of Djoser is a series of stone mastabas stacked on top of each other. Pyramids were built during the Old and Middle Kingdoms, but later rulers abandoned them in favor of less conspicuous rock-cut tombs.[134]

The domestic dwellings of elite and ordinary Egyptians alike were constructed from perishable materials such as mud bricks and wood, and have not survived. Peasants lived in simple homes, while the palaces of the elite were more elaborate structures. A few surviving New Kingdom palaces, such as those in Malkata and Amarna, show richly decorated walls and floors with scenes of people, birds, water pools, deities and geometric designs.[132] Important structures such as temples and tombs that were intended to last forever were constructed of stone instead of bricks. The architectural elements used in the world's first large-scale stone building, Djoser's mortuary complex, include post and lintel supports in the papyrus and lotus motif.

The earliest preserved ancient Egyptian temples, such as those at Giza, consist of single, enclosed halls with roof slabs supported by columns. In the New Kingdom, architects added the pylon, the open courtyard, and the enclosed hypostyle hall to the front of the temple's sanctuary, a style that was standard until the Graeco-Roman period.[133] The earliest and most popular tomb architecture in the Old Kingdom was the mastaba, a flat-roofed rectangular structure of mudbrick or stone built over an underground burial chamber. The step pyramid of Djoser is a series of stone mastabas stacked on top of each other. Pyramids were built during the Old and Middle Kingdoms, but later rulers abandoned them in favor of less conspicuous rock-cut tombs.[134]

Art

Main article: Art of Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptians produced art to serve functional purposes. For over 3500 years, artists adhered to artistic forms and iconography that were developed during the Old Kingdom, following a strict set of principles that resisted foreign influence and internal change.[135] These artistic standards—simple lines, shapes, and flat areas of color combined with the characteristic flat projection of figures with no indication of spatial depth—created a sense of order and balance within a composition. Images and text were intimately interwoven on tomb and temple walls, coffins, stelae, and even statues. The Narmer Palette, for example, displays figures which may also be read as hieroglyphs.[136] Because of the rigid rules that governed its highly stylized and symbolic appearance, ancient Egyptian art served its political and religious purposes with precision and clarity.[137]Ancient Egyptian artisans used stone to carve statues and fine reliefs, but used wood as a cheap and easily carved substitute. Paints were obtained from minerals such as iron ores (red and yellow ochres), copper ores (blue and green), soot or charcoal (black), and limestone (white). Paints could be mixed with gum arabic as a binder and pressed into cakes, which could be moistened with water when needed.[138] Pharaohs used reliefs to record victories in battle, royal decrees, and religious scenes. Common citizens had access to pieces of funerary art, such as shabti statues and books of the dead, which they believed would protect them in the afterlife.[139] During the Middle Kingdom, wooden or clay models depicting scenes from everyday life became popular additions to the tomb. In an attempt to duplicate the activities of the living in the afterlife, these models show laborers, houses, boats, and even military formations that are scale representations of the ideal ancient Egyptian afterlife.[140]

Despite the homogeneity of ancient Egyptian art, the styles of particular times and places sometimes reflected changing cultural or political attitudes. After the invasion of the Hyksos in the Second Intermediate Period, Minoan-style frescoes were found in Avaris.[141] The most striking example of a politically driven change in artistic forms comes from the Amarna period, where figures were radically altered to conform to Akhenaten's revolutionary religious ideas.[142] This style, known as Amarna art, was quickly and thoroughly erased after Akhenaten's death and replaced by the traditional forms.[143]

Religious beliefs

Main article: Ancient Egyptian religion

Beliefs in the divine and in the afterlife were ingrained in ancient Egyptian civilization from its inception; pharaonic rule was based on the divine right of kings. The Egyptian pantheon was populated by gods who had supernatural powers and were called on for help or protection. However, the gods were not always viewed as benevolent, and Egyptians believed they had to be appeased with offerings and prayers. The structure of this pantheon changed continually as new deities were promoted in the hierarchy, but priests made no effort to organize the diverse and sometimes conflicting creation myths and stories into a coherent system.[144] These various conceptions of divinity were not considered contradictory but rather layers in the multiple facets of reality.[145]

Gods were worshiped in cult temples administered by priests acting on the king's behalf. At the center of the temple was the cult statue in a shrine. Temples were not places of public worship or congregation, and only on select feast days and celebrations was a shrine carrying the statue of the god brought out for public worship. Normally, the god's domain was sealed off from the outside world and was only accessible to temple officials. Common citizens could worship private statues in their homes, and amulets offered protection against the forces of chaos.[146] After the New Kingdom, the pharaoh's role as a spiritual intermediary was de-emphasized as religious customs shifted to direct worship of the gods. As a result, priests developed a system of oracles to communicate the will of the gods directly to the people.[147]

The Egyptians believed that every human being was composed of physical and spiritual parts or aspects. In addition to the body, each person had a šwt (shadow), a ba (personality or soul), a ka (life-force), and a name.[148] The heart, rather than the brain, was considered the seat of thoughts and emotions. After death, the spiritual aspects were released from the body and could move at will, but they required the physical remains (or a substitute, such as a statue) as a permanent home. The ultimate goal of the deceased was to rejoin his ka and ba and become one of the "blessed dead", living on as an akh, or "effective one". In order for this to happen, the deceased had to be judged worthy in a trial, in which the heart was weighed against a "feather of truth". If deemed worthy, the deceased could continue their existence on earth in spiritual form.[149]

Burial customs

Main article: Ancient Egyptian burial customs

The ancient Egyptians maintained an elaborate set of burial customs that they believed were necessary to ensure immortality after death. These customs involved preserving the body by mummification, performing burial ceremonies, and interring, along with the body, goods to be used by the deceased in the afterlife.[139] Before the Old Kingdom, bodies buried in desert pits were naturally preserved by desiccation. The arid, desert conditions continued to be a boon throughout the history of ancient Egypt for the burials of the poor, who could not afford the elaborate burial preparations available to the elite. Wealthier Egyptians began to bury their dead in stone tombs and, as a result, they made use of artificial mummification, which involved removing the internal organs, wrapping the body in linen, and burying it in a rectangular stone sarcophagus or wooden coffin. Beginning in the Fourth Dynasty, some parts were preserved separately in canopic jars.[150]By the New Kingdom, the ancient Egyptians had perfected the art of mummification; the best technique took 70 days and involved removing the internal organs, removing the brain through the nose, and desiccating the body in a mixture of salts called natron. The body was then wrapped in linen with protective amulets inserted between layers and placed in a decorated anthropoid coffin. Mummies of the Late Period were also placed in painted cartonnage mummy cases. Actual preservation practices declined during the Ptolemaic and Roman eras, while greater emphasis was placed on the outer appearance of the mummy, which was decorated.[151]

Wealthy Egyptians were buried with larger quantities of luxury items, but all burials, regardless of social status, included goods for the deceased. Beginning in the New Kingdom, books of the dead were included in the grave, along with shabti statues that were believed to perform manual labor for them in the afterlife.[152] Rituals in which the deceased was magically re-animated accompanied burials. After burial, living relatives were expected to occasionally bring food to the tomb and recite prayers on behalf of the deceased.[153

Military

Main article: Military history of Ancient Egypt

The ancient Egyptian military was responsible for defending Egypt against foreign invasion, and for maintaining Egypt's domination in the ancient Near East. The military protected mining expeditions to the Sinai during the Old Kingdom and fought civil wars during the First and Second Intermediate Periods. The military was responsible for maintaining fortifications along important trade routes, such as those found at the city of Buhen on the way to Nubia. Forts also were constructed to serve as military bases, such as the fortress at Sile, which was a base of operations for expeditions to the Levant. In the New Kingdom, a series of pharaohs used the standing Egyptian army to attack and conquer Kush and parts of the Levant.[154]

Typical military equipment included bows and arrows, spears, and round-topped shields made by stretching animal skin over a wooden frame. In the New Kingdom, the military began using chariots that had earlier been introduced by the Hyksos invaders. Weapons and armor continued to improve after the adoption of bronze: shields were now made from solid wood with a bronze buckle, spears were tipped with a bronze point, and the Khopesh was adopted from Asiatic soldiers.[155] The pharaoh was usually depicted in art and literature riding at the head of the army, and there is evidence that at least a few pharaohs, such as Seqenenre Tao II and his sons, did do so.[156] Soldiers were recruited from the general population, but during, and especially after, the New Kingdom, mercenaries from Nubia, Kush, and Libya were hired to fight for Egypt.[157]

Typical military equipment included bows and arrows, spears, and round-topped shields made by stretching animal skin over a wooden frame. In the New Kingdom, the military began using chariots that had earlier been introduced by the Hyksos invaders. Weapons and armor continued to improve after the adoption of bronze: shields were now made from solid wood with a bronze buckle, spears were tipped with a bronze point, and the Khopesh was adopted from Asiatic soldiers.[155] The pharaoh was usually depicted in art and literature riding at the head of the army, and there is evidence that at least a few pharaohs, such as Seqenenre Tao II and his sons, did do so.[156] Soldiers were recruited from the general population, but during, and especially after, the New Kingdom, mercenaries from Nubia, Kush, and Libya were hired to fight for Egypt.[157]

0 comments:

Post a Comment